“I don’t think anyone could make a legitimate theater in Los Angeles a profitable venture.” – James A. Doolittle, Director Huntington Hartford Theater and The Greek Theater.” – 1964

Just like Tara, it was the land that mattered most. And for the Wilkes Brothers, two allegedly wealthy mid-west oilmen, investing in real estate’s increasing value, was the way to go.

The brothers partnered with Cecil B. DeMille in building a theater at 1735 North Vine Street above Hollywood Boulevard. When the deal fell through, the Wilkes brothers took their money and the architectural plans of Myron C. Hunt and H. C. Chambers immediately moving the site of their new theater further down Vine Street near the corner of Selma avenue. On 09 March, 1926, immediate construction began after landowner Jacob Stern leased the site property located at 1613-1619 Vine to Frank R. Strong and John F. Wilson for a 99 year term at a rental costing $1,692,000. The theater ‘s combined cost including house and furnishings estimated at $500,000.

The construction of the Wilkes Vine Street Theater, April 1926.

Famous Players-Lasky Movie Studio is seen upper left while The Hollywood Rooftop Ballroom is seen on the upper right, the current location of Bed, Bath & Beyond. Photos USC

The Wilkes Vine Street Theater and Shops nearing completion in late 1926.

Photo USC Collection.

Wilkes Vine Street Theater nearing completion in November, 1926

The theater was leased to Alfred Galpin and Thomas Wheaton Wilkes for the production of legitimate plays, at a twenty year rental costing $1,275,000. Said Wilkes: “I am optimistic over this enterprise. If I were opening a theater downtown at the present time, I might be trembling over the outcome. But here I feel perfectly sanguine as regards the future. The more theaters that Hollywood has, the more it will attract the theatergoing public.

“In this playhouse we are attempting to cater only to a very discriminating audience. We feel that the location is ideal, The availability of parking space enters into this very largely, because it is undoubted that a great number of our patrons will motor to this theater. The Vine Street will be easily accessbile to this group of people since it is situated on a main traffic highway. Nor is it more than a step from the streetcar for those who use that means of transportation”

By 1926, Hollywood was becoming modern in its approach to architecture and design. The Vine Street interior, supervised by Dickson Morgan, the theater’s technical director, was made charming by virtue of its simplicity. A neutral shade of brown carpeting dominated while the seating blended red with delicate stripes of gold. The balcony lounge was decorated primarily in green and the balcony design gave the illusion of jutting right out close to the stage. Because of the closeness of the balcony to the stage, as well as the slope of the floor, set height was limited to not taller than eight feet. The conventional frame around the proscenium was eliminated and the footlight lighting synchronized with the rising of the curtain, eliminating lights shining on the curtain.

The theater, lit by two crystal chandeliers, a minimum of side and drop lights enhanced the theater’s warmth and the ceiling, suggesting the oriental note in its use of pastel shades which are also carried out in the lighting. The entire auditorium was completely modern.

The opening night premiere in January 1927 was a gala arc-light affair attended by the who’s who of the film industry with authoress, Adela Rogers St. John as mistress of ceremonies and well wishes from President Taft for the success of the Vine-Hollywood area.

The rear auditorium of the Vine Street Theater in 1926. Two large crystal chandeliers flank both sides of the auditorium.

The first play Wilkes chose was a controversial staging of Theodore Dreiser’s “An American Tragedy” starring a much-talked-about actor named Leslie Fenton. Fenton’s first night performance, before the elite of first-nighters, received such enthusiastic applause he stopped the staging with a few words of appreciation. Within days, the city prosecutor received complaints that An American Tragedy contained obscene portions, most notably a bedroom scene. While agreeing to modify the scene, Wilkes asserted the play “had great moral purpose” and invited ministers to view it. Controversy fueled the box-office

Despite what was to come, A. G. Wilkes was an excellent managing director of the Vine Street Theater. One after the other he secured among his plays: Broadway, An American Tragedy, The Captive with Helen Menken and Basil Rathbone and The Noose. It was he who brought out a New York director to handle the twelve scenes and large cast of An American Tragedy as well as insisting that none of the controversial scenes be cut. Management proposed a panel of clergy, doctors, lawyers, journalists and club women in deciding censorship of any play. “How much better that would be than having the police decide what we shall see and what shall be taboo,” Wilkes said.

New York stage actors, brought to Hollywood by motion picture producers, doubled in both stage and motion picture work when appearing at the Vine Street Theater. In rapid succession stars crossing the footlights included: Helene Millard, Leslie Fenton, Joseph Schildkraut, Nana Bryant, William B. Davidson, Henry Kolker (also directing), Glenda Farrell, Barbara Luddy, Barbara Brown, Allen Vincent, Lois Wilson, Maurice Costello, Florence Eldridge whose husband, Fredric March, was starring in The Royal Family of Broadway at the Pasadena Playhouse.

In July 1927, telephoned death threats and acts of violence were threatened by the actor’s union against the Vine Street Theater for presenting popular plays with non-union actors. Raymond Hitchcock, actor and theater investor in the production of the musical The Geisha, was threatened by Actor’s equity that he could not work on stage with non-union actors. If Hitchcock appeared in any capacity, he would be shot, according to a telephone call he received. Unlike George M. Cohan, who closed his theaters rather than bow to Actor’s Equity, Mr. Hitchcock decided against appearing. “I came here thinking to have an interest in the production but found an impossible situation and I can’t do it. I’d be suspended from the stage for five years if I did.”

The theater offered to make the entire cast Equity but equity refused membership saying they already had enough Equity members for whom they want work. Refusing new members was a right granted in the Equity agreement with producers. The cast the producers selected had better voices and a fresher appearance than the chorus girls Equity wanted cast but Equity said it acted within its rights because producers would not guarantee two-weeks salary and refused to put up a bond for the salary guarantee.

Although Hitchcock did not appear in the play, the opening n ight house was planted with hoodlums intent upon disturbing the performance with all manner of noises. Management decided performances would continue despite any action Equity might take as a fight to the finish for independence and freedom of labor against union tyranny.

The theater went dark for a time in the summer of 1927 then re-opening in November re-dedicated as a theater producing original plays only. Edward Clark, the new lessee and managing director decided that with the amount of local writers available, several promising new plays might be developed. Clark then wrote and acted in his own play “Relations,” a comedy with Jewish-American characters.

By 1928, Alfred G. Wilkes had passed through voluntary bankruptcy, listing his liabilities as nearly $1,000,000, and his assets as $2358. His creditors received .0119 cents on the dollar. A year later, Wilkes was indicted by a federal grand jury for tax fraud for “willful” failure to pay $16,464.50 due on the receipts of the Wilkes Theater in San Francisco (now, The Geary Theater) and given a suspended sentence and three years to clear his debt. Wilkes failed to pay the government the 10 percent amusement tax then demanded on all theater tickets, diverting the funds for his personal use. Then, Wilkes and 16 Oil executives of the Italo Petroleum Corporation were ordered to stand trial for mail fraud and conspiracy to commit mail fraud. Although claiming personal bankruptcy, it was discovered that distribution of approximately $10,000,000 in secret profits were made to Wilkes and sixteen other officers and directors of the oil company. Wilkes paid $55,000 to buy off a judge hearing his case and had hidden 156,783 shares of common stock, 2,070 shares of preferred stock and $186,088 in cash.

Wilkes was given two years prison sentence and $5,000 on the conspiracy count and one year prison sentence and $1000 fine each of two mail fraud counts, sentences to run concurrently. Wilkes appealed the sentences and died 16 February 1937 at age 57 before resolution. His brother, Thomas W. Wilkes passed away the year before.

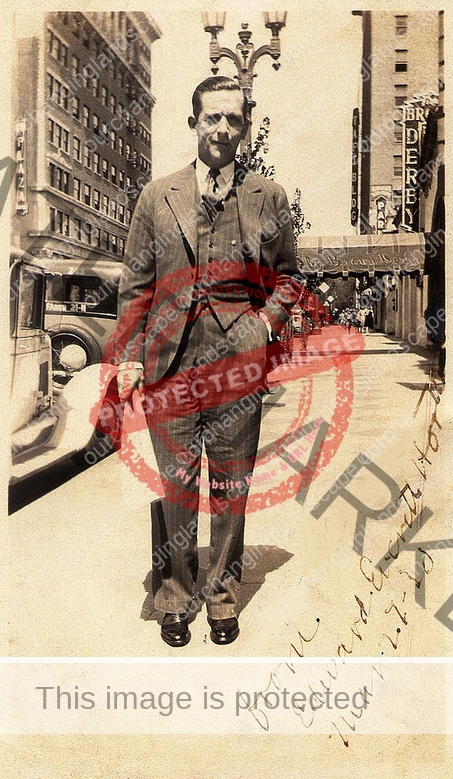

Edward Everett Horton across from the Vine Street Theater in March 1930. B. H. Dyas Department store is seen in the upper left and the Brown Derby on the right.

The theater changed hands in February 1928 when Edward Everett Horton took over management of the Vine Street Theater. Wilkes name was removed from the side marquees with a new electric sign replacing it. Horton augmented his stock company of actors with his theater friends and the best material available. Among his actors were Marie Dressler, Lois Wilson, Allen Vincent, Leatrice Joy, Florence Eldridge, Ralph Forbes and a varied diet of ARMS AND THE MAN, HER CARDBOARD LOVER, THE SWAN, ON APPROVAL and THE GOSSIPY SEX.

After a year, Horton vacated the final months of his contract and moved downtown to the MAJESTIC, turning his lease over to S. George Ullman and Associates bowing in a play, WEAK SISTERS, with Franklin Pangborn and Priscilla Dean. Although loath to explain the reason for his quick departure, Horton later admitted that the matinee business was not strong in Hollywood. Matinee business at The Swan was excellent but other plays were less successful. The matinee trade is important with expensive productions, casts of well-known and highly paid supporting players. “I think about two weeks exhausts the business from this district. Another factor was a lack of casual drop-in trade.” By the end of 1929, Horton had abandoned Edward Everett Horton Productions, deciding to concentrate solely on his film career. “There are leagues for everything else under the sun, but the theater which lies so close to our hearts is left to get along the best it may. It’s friends have nothing to say. Only enemies speak against it with their demands of censorship which will eventually strangle it,” Horton said.

Franklin Pangborn took over the remainder of Horton’s lease in February 1929 investing in and appearing in original productions. Pangborn played the part of Roy Lane, a hoofer of meager talent but saturated with egotism and ambition in BROADWAY. Pangborn hired Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. to make his third stage appearnce, this in a Phillip Barry comedy-drama, THE YOUNGEST. Marjorie Rambeau appeared in MERELY MARY ANN and WHAT A WOMAN WANTS. Pangborn left the Vine Street in December 1929 but the theater continued with some fine plays, most notably ROPE’S END with Dwight Frye in a grimly suspenseful intellectual murder play similar to the Leopold and Loeb case in Chicago.

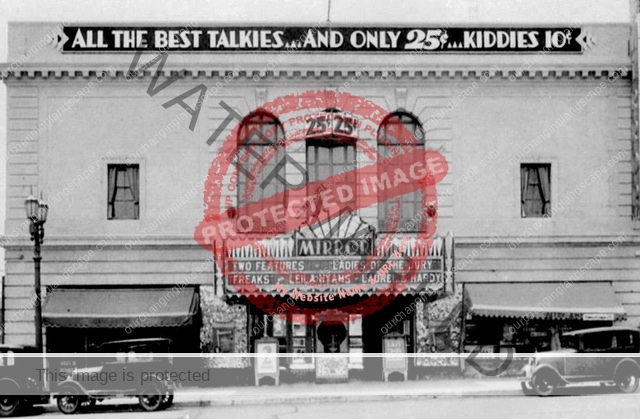

Another hit play, PHILADELPHIA was cut short after three weeks when the Vine Street Theater was sold for $800,000 to a syndicate of Vancouver capitalists intent upon replacing the theater with a 13 story Class “A” office building, adding eleven stories to the present theater structure. The capitalists also purchased a site next to the Brown Derby building for $250,000 for a hotel for women as well as spending $620,000 for the northeast corner of Vine and Selma for a 13 story hotel. As the Great Depression deepened, nothing came of these plans and on Christmas Day 1930, the Vine Street theater began showing movies at the bargain rate of 25 cents.

The Vine Street Theater on March 30, 1930 with the opening of PHILADELPHIA. The theater boasts a new marquee and illuminated vertical signs.

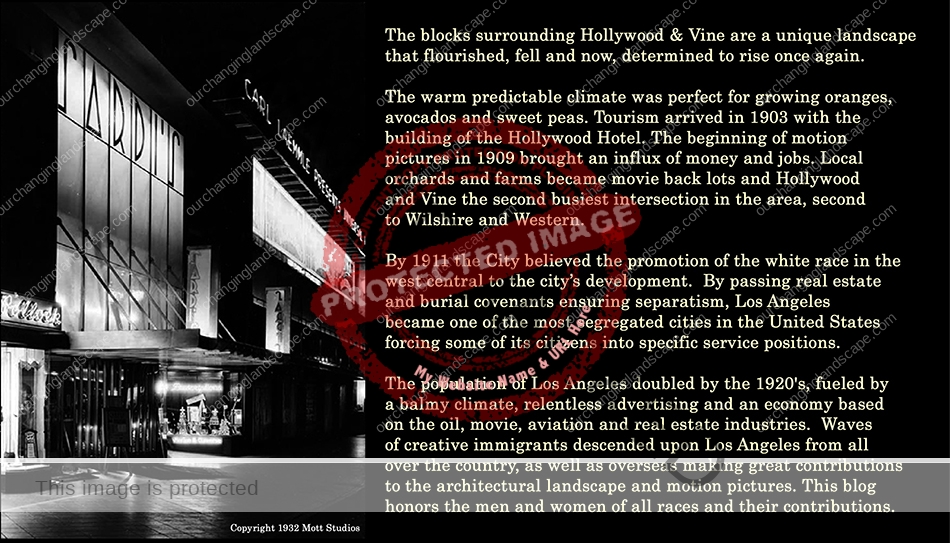

With a new marquee and showing ‘All The Best Talkies–and only 25 Cents’ (1932) LAPL