THE FIVE-FINGER PLAN

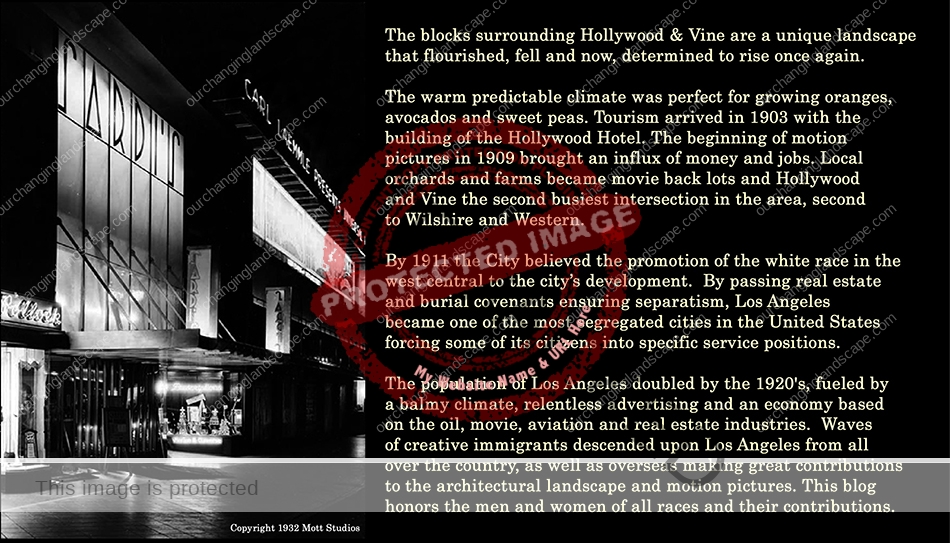

Looking north from Hollywood and Vine, 1907. A. G. Bartlett estate is on the left.

Like most cities of Spanish origin, Los Angeles had its first growth about its downtown plaza. Hollywood’s real estate development began during the American Civil War, when Jose Valdez acquired 1000 acres of the Spanish grant of Antonio Rocha, until American settlers dispossessed Valdez and Tomas Urquidez on legal technicalities.

In 1888, Horace Wilcox began laying out the town on his 640 acres, and Senator Cornelius Cole began subdividing Colegrove, now the southern part of Hollywood, but lots sold poorly and the town grew slowly.

There were only 500 people in this shepherds’ village, which was incorporated in 1903 and annexed in 1910. The best peas in Hollywood were growing on the Famous Players-Lasky lot at Vine between Selma and Sunset before the movies took possession of the tract in 1913.

With Eastern expansion gradually moving westward, Hollywood became one of the outstanding examples of an influence that changed city growth: city planning.

The decentralization of the downtown business district, due to excessive automobile congestion, and its subsequent re-location to outlying underdeveloped land such as Hollywood was the city’s first gentrification attempt. By systematically moving “undesirables” to outlying communities Hollywood’s select real estate remained accessible only to the white wealthy. By 1925, Hollywood shops rivaled the best in downtown Los Angeles. In 1925, the average value of property on Hollywood between Wilcox and Argyle was $4000 a front foot with a predicted increase to $10,000 a front foot by 1935.

The 100 x 150 feet lot on the southwest corner of Hollywood and Vine sold in 1922 for $100,000 and, by 1925, its value increased to $400,000. The land, which in many locations, is desert and thought unfit for agricultural production, became fertile with proper cultivation and irrigation.

Closely identified with the development of Hollywood is Alfred Z. Taft owner of a prominent Hollywood real estate syndicate, the Taft Realty Company of Hollywood. By 1920, several large Taft subdivided several tracts, among them Taft’s West Hollywood Vista tract, located in the most exclusive residential section of West Hollywood.

Taft’s extensive ownership of commercial and agricultural real estate in Hollywood and his Hollywood improvement plan also created these “restricted” and “exclusive” neighborhoods throughout Los Angeles in keeping with the conventional wisdom of the period.

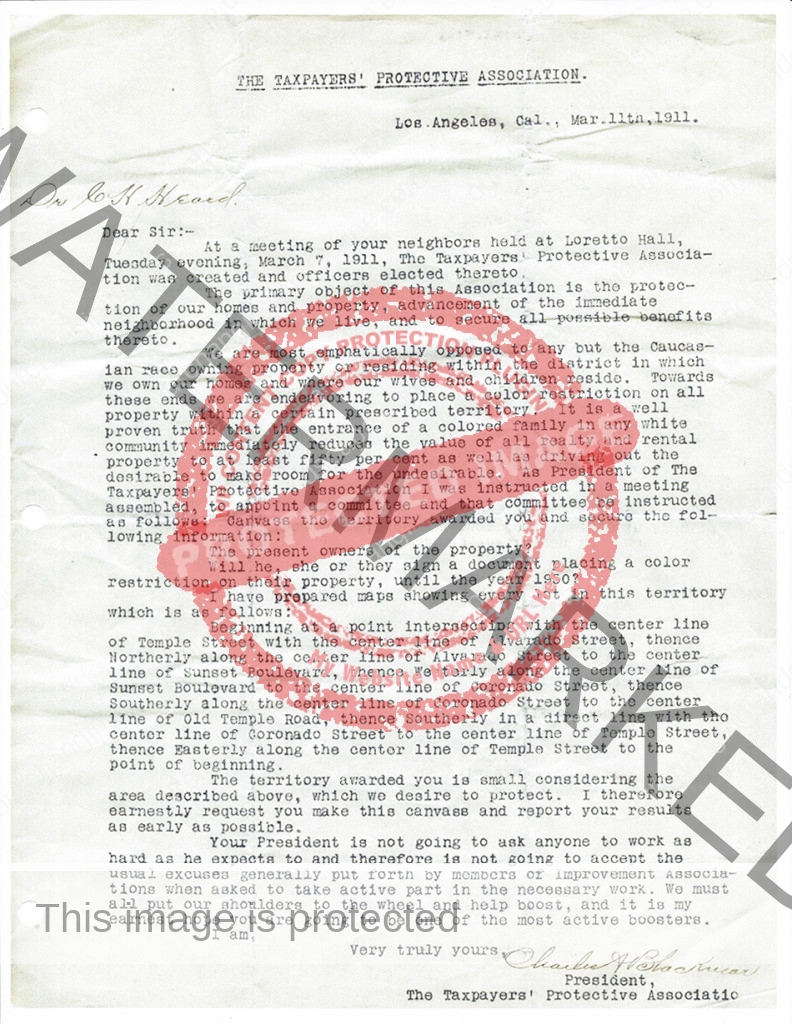

The Taxpayer’s Protective Association set up racial covenants in 1911. The first recorded racial covenant since Hollywood became a city was in 1909.

Establishing a record price for Hollywood Boulevard frontage, the Taft realty company purchased the southeast corner of Vine Street and Hollywood Boulevard on 24 April 1921, the site of the First Methodist Episcopal Church, South, for more than $125,000. Of the 120 feet frontage, forty feet was available for immediate sale, with the remaining 80 feet held as a site for a proposed store and office building.

Large Eastern oil companies such as the Barnsdall Corporation begun buying land and subdividing into exclusive residential and business districts such as Olive Hill, a community boarded by Santa Monica Blvd, Hollywood Blvd., Vermont Avenue and Edgemont Street. Each district was to have an exclusive shopping district, with homes and a theater seating 500-600, offered to the Hollywood Theater Association. Architect Frank Lloyd Wright supervised all architectural work, including designing of the buildings and landscaping.

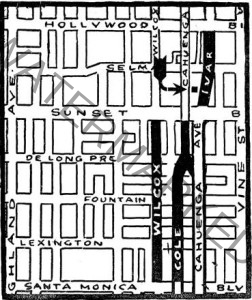

The Five-Finger Plan extended Cole and Wilcox below Hollywood Boulevard and widened Cahuenga Boulevard.

Property owners in an 1800-acre area in the Hollywood foothills threw their support behind the Five-Finger Plan, a proposed $3,700,000 boulevard widening system for Hollywood. “The Five-Finger Plan” was one of the first major street plans approved by Los Angeles voters. The first phase of the plan widened Cahuenga Boulevard from 50 to 94 feet. Paving and widening of Selma Avenue in Hollywood from Highland to Gower began in September 1925, costing $500,000 according to the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. The “Five-Finger Plan” included linking Hollywood with the San Fernando Valley.

Along with street widening and paving, building construction increased. Projects included the one-million-dollar Warner Brothers Theater at the corner of Hollywood and Wilcox, a new post-office on the west side of Vine Street above Hollywood, The Rooftop Ballroom at Selma and Vine, costing $150,000, The Plaza Hotel on the Southwest corner of Vine Street and Hollywood Boulevard and the Marion Building on Selma and Vine built for Frank Marion.

By condemning land and then seizing it, the city gained land necessary for road expansion. The city defends the practice, now known as ‘eminent domain,’ as necessary for the betterment of the city, and “reasonable” compensation paid as fair and just. Donating the land was an option few enjoy, then and now.

Although condemnation made possible road widening, power line installation and installation of water or sewer lines on, over or beneath land adjacent to existing government improvements, the practice is controversial when used for projects with questionable public value.

Accompanied by the growing financial solidarity of the motion picture industry, Hollywood’s grew rapidly. By 1925, attendance at movie theaters averaged 70 million attendees weekly and audiences expected the movie folk to live opulent lifestyles.

Hollywood area development, overseen by the Vine Street Development Association, provided for a systematic development of the district with plans calling for the establishment of the Vine Street area as a great shopping and theatrical center. Nineteen twenties women preferred shopping in Hollywood to driving downtown unable to find parking. Intersections of important highways always form a nucleus for potential business districts, where land values soar.

By June 1930, the Hollywood-Vine area saw seven limit-height structures, The Bank of Hollywood, Guaranty, Taft, Dyas, Plaza, Knickerbocker Hotel and Mountain States Life Building, built since 1924, establishing a record for communities located outside of downtown metropolitan areas. By the fall of 1929, Hollywood had sixteen motion picture and four legitimate theaters. More than $50 million dollars was set aside for building construction and another $8 million for street improvements in the next two years.

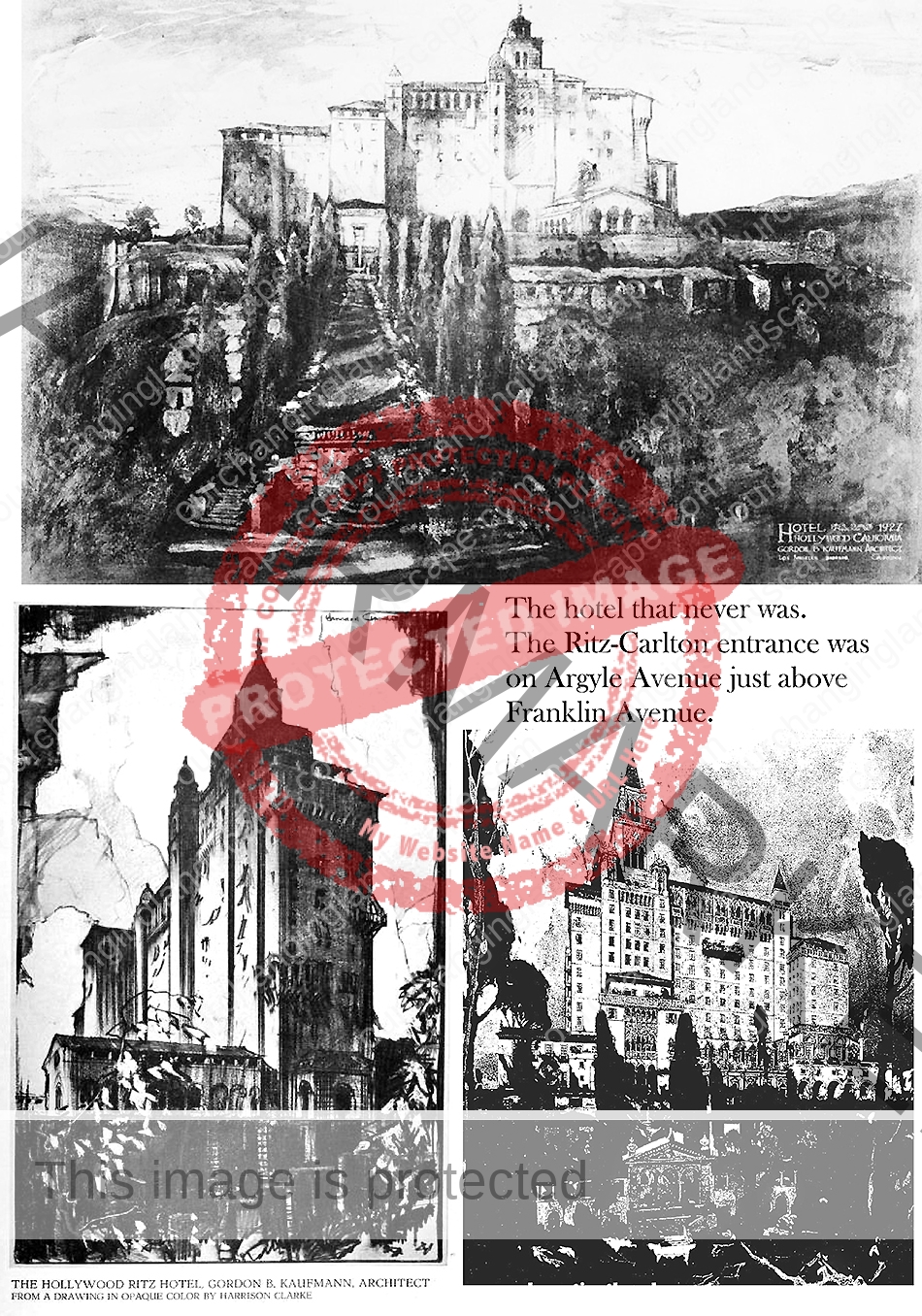

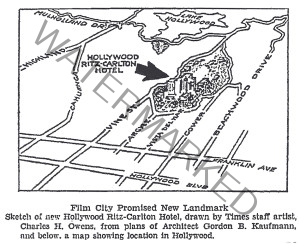

Eliminating the Vine street hill upwards from Yucca prepared for the building of a $5,000,000 Ritz-Carlton Hotel. This 250 room, 100 bungalows, Ritz-Carlton, set to rise in the Hollywood Hills would be the first in the chain in California and the crowning glory of the chain. The 22-acre hilltop site, with magnificent views overlooking the mountains and the sea and lying between Beachwood drive and Vine Street had a built in wealthy clientele beneficial to the Los Angeles area by an increase in property values. A drafting office erected on the site in March 1930, expected that more than investors would spend $100,000,000 building hotels and apartments adjoining the Ritz Carleton site prior to the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

On April 18, 1930, the Ritz-Carleton Corporation approved architect Gordon B. Kaufman’s Spanish-style plans with the caveat the hotel must be ready for opening no later 31 March 1931. Within five years, frontage on Hollywood Blvd. could possibly reach $20,000 per front feet. Hollywood Business Properties, owners of a mile of Hollywood Blvd. Frontage paid a 200 percent cash dividend to stockholders of record on April 1, 1930, remarkable during a period of the Great Depression. Following the announced of the building of a new Ritz-Carlton hotel, there was an immediate increase in one-way tickets to Los Angeles from the East, indicating an incoming permanent influx of new residents.

On April 18, 1930, the Ritz-Carleton Corporation approved architect Gordon B. Kaufman’s Spanish-style plans with the caveat the hotel must be ready for opening no later 31 March 1931. Within five years, frontage on Hollywood Blvd. could possibly reach $20,000 per front feet. Hollywood Business Properties, owners of a mile of Hollywood Blvd. Frontage paid a 200 percent cash dividend to stockholders of record on April 1, 1930, remarkable during a period of the Great Depression. Following the announced of the building of a new Ritz-Carlton hotel, there was an immediate increase in one-way tickets to Los Angeles from the East, indicating an incoming permanent influx of new residents.

However, building on the Ritz-Carlton could not occur without a zoning change from single-family residences to commercial. Building Authorization, granted on 16 June 1930, followed a dinner held under a canvas top for 200 prominent business and civic leaders. Twenty huge multi-colored searchlights punctuated by the Goodyear blimp filled the sky with what witnesses described as “one of the greatest single electrical displays in history.”

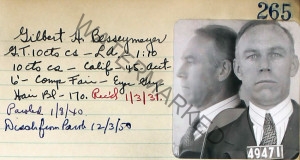

The feature of the program was a fifteen-minute address delivered by George McAneny, President of the Ritz-Carlton chain, speaking over the telephone from his New York office, broadcast through large speakers. At the end of the speech, McAneny exchanged greetings with Gilbert Beesemyer, president of the Hollywood Ritz-Carlton, and Harry Chandler and S. H. Woodruff, directors.

In 1925, Gilbert Henry Beesemyer was president of Central Bank of Hollywood as well as secretary and general manager of Guaranty Building and Loan Association. By 1929, Beesemyer along with B. H. Dyas, Sid Grauman, Carl Laemmle, Joseph M. Schenck and Sol Lesser were part of a network of leading Hollywood Directors.

However, on 12 Dec 1930, at a meeting of the Board of Directors of the Bank of Hollywood, Beesemyer admitted embezzling funds amounting to more than $8,000,000 from their ally, The Guaranty Building and Loan Association of Hollywood, leaving a trail of want and suicide among the 25,000 stockholders worldwide caught in the firm’s collapse.

Plans for a Ritz-Carlton in Hollywood disappeared immediately without explanation.

Three days later the Bank of Hollywood closed its doors and Beesemyer admitting falsifying records of the North American Bond & Mortgage Co. and the Guaranty Holding Corporation and putting more than $2,000,000 into the Elmer Oil Company of Santa Fe Springs. After drilling eleven dry wells, the company failed. Beesemyer also suffered losses of about $600,000 in the stock market and $400,000 from personal loans.

Bessemeyer (listed as Besseymeyer in his San Quentin record, served 9 years for embezzling $8 million dollars.

Convicted on 10 counts of grand theft on 31 January 1931, the court sentenced Bessemyer to from 10 to 40 years in San Quentin. After serving 9 years, twice as long as any man ever served in California for a similar offense, Beesemyer gained parole in January 1940 due to existing laws and against public outcry. Beesemyer left prison with permission to leave the state for a job in Chicago. In 1942, Bessemyer was living in Baltimore, Md. and working for the Livingston Chemical Company. He eventually returned to Ventura County, California where he died on 22 Feb 1982 at the age of 97. At that time of his release from prison, investors suspected Bessemyer had more than $1,000,000 in hidden assets.

By 1934, traffic jams in the Hollywood/Vine area were commonplace.

By 1931, widening of Hollywood Boulevard, Vine Street, Ivar Avenue, Cahuenga Blvd. and Cole from 70 to 100 feet was complete. Ivar between Hollywood Blvd. and Selma Street, Ivar created below Hollywood Blvd. by the “Five-finger Plan,” was to be a bond house area with negotiations with bond houses; buildings constructed to suit. Vine Street was to be the main artery south to Wilshire Boulevard, while Cahuenga would carry heavy traffic going north into the valley. However, Hollywood’s population growth far exceeded what it could handle. Hollywood and Vine was, by 1934, one of the most heavily traveled areas in Los Angeles. City planners turned their attention to Wilshire Boulevard as the most desirable location for high end shopping. I Magnin moved its flagship store from the corner of Hollywood and Vine to an elegant Wilshire Boulevard location.

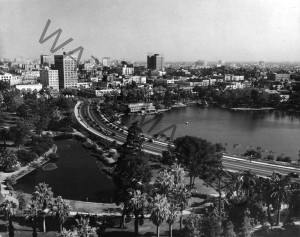

Once Wilshire Boulevard was extended through MacArthur Park in 1934, Wilshire Boulevard became the fashionable shopping district.

The completed passthrough of Wilshire Boulevard through MacArthur Park.

Not all of this expansion went unnoticed by residents. In February 1933, residential property owners in the Hancock Park, Windsor Square, Piedmont Place and Wilshire Crest districts organized a new civic development association known as the Wilshire Home Owners Association, with an avowed program of saving Wilshire Boulevard from becoming a “pig-stand sandwich alley.” Their pledge was in maintaining the high class residential character of the area located between Western and LaBrea avenues, vowing to prevent this section from being zoned for Business use. Once Wilshire Boulevard was opened through MacArthur Park in 1934, Wilshire became a major link to downtown as well as an exclusive shopping district. Widening Wilshire to more than 70 feet with parking available on both sides of the street gave rise to rapid expansion of luxury shopping areas.

Road widening at Sunset and Vine, 1930.

On January 31, 1931, William M. Davey, a heavy investor in Hollywood properties, purchased the newly opened Bank of Hollywood building for $1,500,000, moving his office into one of the buildings 321 offices, giving it the largest office capacity of any building in the area. Many downtown financial houses moved into the building creating 100% occupancy showing office space in the area is in strong demand.

Notwithstanding the depressions that intervened from 1880 to 1932, the value of Los Angeles real estate doubled in each of the five decades, making investors rich. Others were not so lucky.

Gentrification, revived in the Vine Street area with the building of The Camden Apartments, a RIT, at 1590 Vine at Selma, with rents starting at $2,205 for a studio unit up to a $4,070 monthly starting rental for a two bedroom-two bath unit, continues a path of neighborhood displacement of lower income families, seniors and small business owners. There are no affordable housing units available in this new luxury apartment building. Residents in the Vine Street area find themselves not only in a neighborhood they no longer recognize but also one in which they cannot afford active participation.

Vine at Sunset, 1925. Famous Players-Lasky Motion Picture Studio is on the left.

Photo Credit: California Historical Society (USC)

Sunset Boulevard in September 1931 after street widening. Photo Credit: California Historical Society (USC)